Banks have felt pressure in recent years from investors and environmental groups to curtail their financing of fossil fuel exploration. Now some of those groups are urging lenders to reexamine their relationship with the plastics industry.

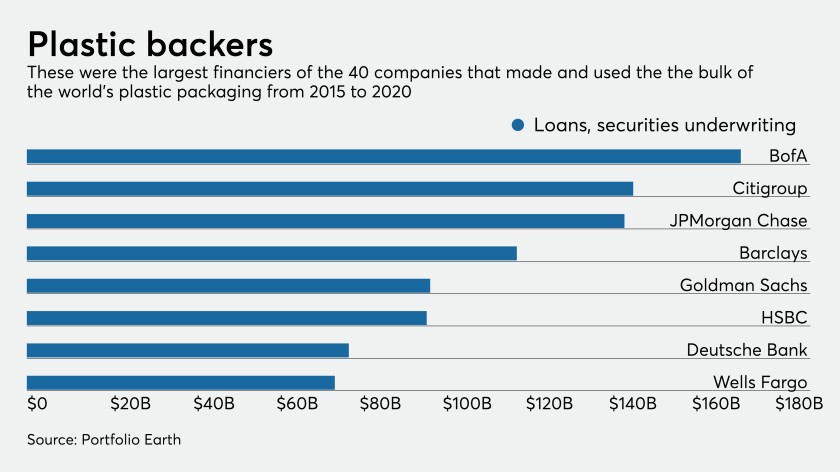

Banks’ financing of the largest actors in the plastics supply chain — without any sustainability criteria attached — make them partly responsible for the tons of water bottles and other packaging cluttering the globe, an environmental coalition charged in a January report. The group, called Portfolio Earth, named Bank of America, Citigroup and JPMorgan as the three largest financiers of plastic in the world.

“By indiscriminately funding actors in the plastics supply chain, banks have failed to acknowledge their role in enabling global plastic pollution,” the coalition wrote. “They have fallen far behind other [corporate] actors that contribute to the plastic pollution crisis.”

The paper, dubbed “Bankrolling Plastic,” is a sign that banks are being pulled into another raging societal debate over the environment and other matters. And it raises questions about how many more issues will follow, how many causes banks can and should be held accountable for, and whether there is any way for them to get ahead of these controversies.

“Climate change is still one of the top issues, but now banks are supposed to look at plastic footprints and forestry footprints,” said Alexandra Mihailescu Cichon, executive vice president at RepRisk, a data science firm specializing in environmental, social and governance issues in banking. “It’s hard to know where to shift your focus.”

Two hundred sixty-five global banks provided more than $1.7 trillion in financing — either through loans or by underwriting stock and bond issuances — to key players in the plastics industry between January 2015 and September 2020, according to the Portfolio Earth report. The customers were 40 companies that either make, or use for their products, the bulk of the world’s single-use plastic packaging.

More than 80% of the financing came from 20 companies. Three of the banks on that list — BofA, Citi and HSBC — were contacted for this story and didn’t respond or declined to make an executive available for interview.

Environmental activists and some ESG-minded investors say that there’s a strong argument for banks to consider plastic pollution a crisis on par with climate change.

“It’s an easy one to say that plastic deserves attention because the arguments are financial, environmental and social,” said Jonas Kron, chief advocacy officer of the socially responsible investment firm Trillium Asset Management.

Plastic waste has accumulated in virtually every corner of the world, largely thanks to single-use packaging of consumer goods. It kills marine birds and animals, and a garbage patch in the Pacific Ocean has now grown to a surface area twice the size of Texas. Microplastics have made their way into the food supply, too.

While consumers are increasingly concerned about plastic pollution, they also have few options to avoid or recycle it. Less than 9%, or about 3 million tons, of plastic waste generated in 2018 was actually recycled, while 27 million tons wound up in landfills, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

That plastic will take hundreds of years or longer to decompose on its own, and in the meantime it carries serious financial costs for businesses and societies. Governments pay a lot of money to clean it up. Landfills can be expensive to maintain, and they require space that could otherwise be put to more productive use. Plastics pollution can hurt revenue for businesses like fisheries or tourism companies, and it can bring down real estate values in coastal communities.

A 2019 study by Deloitte estimated the direct and indirect costs of marine plastic pollution likely totaled between $6 billion and $19 billion across 87 coastal countries in 2018.

“It’s a serious problem, particularly in oceans,” said Robin Smale, director of Vivid Economics, a London-based consulting firm. Smale, who audited the Portfolio Earth paper, said that banks’ financing of plastic pollution does give them some ownership of the problem.

“If you’re going to tackle that, then you have to address the financial systems’ role in that and not just work at the corporate level or with governments or regulation,” he said.

But how many single issues can the banking industry reasonably be expected to address, particularly at a time when banks are already turning away from other sensitive industries, like oil-and-gas exploration, gun manufacturers or private prisons?

The answer to that question depends somewhat on a concept called materiality, or how much a given company’s stakeholders care about that company acting on a particular issue.

Right now, expectations are fairly low for the banking sector to act on plastic. Outside of the Portfolio Earth report, there’s been little pressure to get involved. When the subject of plastic does come in conversation, investment managers say it’s usually within the context of broader concerns about the ocean and biodiversity.

“Within the banking industry, I really haven’t heard any discussion at all about plastics,” said Mark Fitzgibbon, an analyst at Piper Sandler.

However, the next few proxy seasons could offer a preview of what’s to come for banks and other public companies. The nonprofit group, As You Sow, filed shareholder proposals with 10 major consumer goods companies, including Target, Walmart and PepsiCo, calling on the firms to reduce their use of plastic packaging.

Regulation of single-use plastics could ultimately put more pressure on the banking sector if it makes virgin plastic more expensive for its corporate clients to manufacture. In a research note issued in December, Moody’s Investors Service predicted demand for single-use plastics would fall over the next decade, citing the potential for regulation and greater demand for recycled plastics.

“There is self-interest for companies to solve this problem,” Kron said. “If they don’t then governments may tell them how the problem needs to be solved.”

ESG experts say there’s a fundamental problem with asking how many single environmental issues bankers can be expected to address — largely because the question assumes these issues can be neatly sorted into distinct categories. In other words, plastic pollution isn’t an entirely separate issue from climate change — particularly since the majority of virgin plastic is sourced from fossil fuels.

Still, bankers could gain an advantage by getting a handle on these issues now.

Banks would benefit from approaching issues like plastic as one component of a broader focus on environmental risk management, said Lauren Compere, managing director at Boston Common Asset Management, an environmentally-conscious investment firm.

“Banks need to have in place a process to identify emerging risk issues and then strategize around how to develop an approach,” Compere said.

Blaine Townsend, director of sustainable, responsible and impact investing with the investment management firm Bailard, compared the issue of plastic to that of energy lending. It took a long time to get to the point where big banks started to curtail their financing of fossil-fuel exploration.

“We’re far behind being able to unpack lending in the plastic supply chains to that same extent or that same level,” he said.

Like other ESG issues, getting a handle on plastic will also entail gathering a lot of data. Similar to the way that banks are now beginning to measure the carbon impact of their lending activities, they can collect data about the companies and industries they bank to better understand how much plastic they’re financing, Cichon said. An entire cottage industry, including companies like RepRisk, has grown up around the need for data to help banks measure ESG risks.

“These reports are important as conversation starters and shifting the mindset internally at these organizations, but that takes time until it plays out in their policies and financing decisions,” Cichon said.

To be sure, banks have made solid progress in recent years on a host of environmental issues. Some have pledged to scale back their financing of new coal plants or certain types of fossil-fuel exploration. Others have carved out niches in financing renewable energy, chiefly solar and wind, and still others have sought to cut down on their own water and energy use.

To date, plastic has been largely absent from those environmental efforts, although there are a few examples of banks taking small, initial steps on the issue. For example, water bottle filling stations in its headquarters allowed Citigroup to reduce plastic water bottle usage by about 86,000 per month, though it did not otherwise address plastic in its first ESG report issued last April.

And HSBC in London also served as an adviser and lead manager on a transaction last year in which a German chemical company issued its own plastic waste reduction bond.

Among other steps outlined in its report, Portfolio Earth suggested that banks can start to measure and report on the plastic they may be responsible for financing. They can also pledge to stop financing the production of virgin plastic and make financing to the industry contingent on meeting certain sustainability benchmarks.

The lack of progress on plastics is “not necessarily an indictment” of the banking industry, so much as it is an indication that the issue is still in its infancy, Townsend said.

“The bar would be low for a hero in financial services around plastic because really, there’s been no leadership in financial services on financing the supply chain of plastic,” he said.