Investors are fretting over Treasury yields and wondering when a rate rise could start to crimp a stock-market rally, though they weren’t yet worried enough Tuesday to prevent major benchmarks from notching another round of all-time peaks.

So when does the pain of rising yields, which makes it harder to justify stretched equity valuations, start to make a difference? With the yield on the 10-year Treasury note

TMUBMUSD10Y,

moving back above 1.2%, a challenge of the 1.5% area, which is the equivalent of the dividend yield on the S&P 500

SPX,

could soon be in store, wrote Sean Darby, global head of strategy at Jefferies, in a Tuesday note.

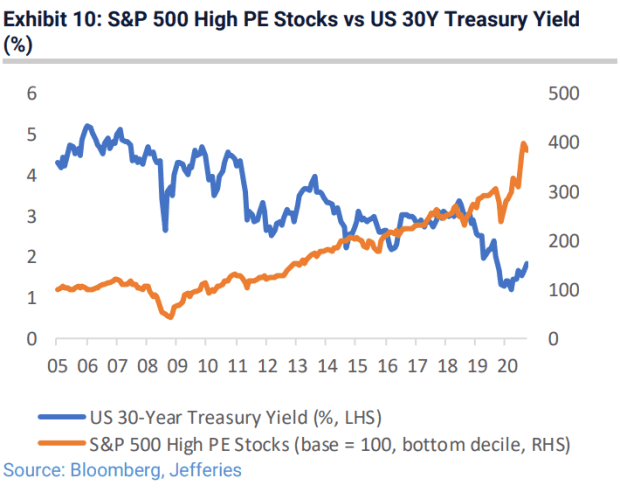

That event “will probably coincide with the first test for the valuations of the higher PE stocks and the relative performance of the S&P 500 versus more loftier valued indices such as the Nasdaq-100,” he wrote, referring to the P/E, or price-to-earnings ratio, a common measure of stock market valuations.

Historically, low Treasury rates have been seen justifying lofty valuations for equities, as investors have little choice but to look to stocks for returns. While Treasury yields remain low, the move higher could threaten equities with the most stretched valuations, strategists have warned. Yields and bond prices move in opposite directions.

But Darby delves deeper, arguing that financial markets have likely undergone a “regime change” as investors adapt to the Federal Reserve’s average-inflation targeting setup, which would see the central bank allow inflation to overshoot its target and the economy to run hot before moving to tighten policy.

That regime change amid expectations for abundant liquidity may be illustrated by the continued rally in junk, or high-yield, corporate bonds. Those yields have fallen sharply, even trading below Treasurys on an inflation-adjusted basis for the first time in history, he noted.

Meanwhile, the U.S. dollar, while seeing a modest bounce to begin 2021, hasn’t yet staged a convincing turnaround after its steep 2020 slide, analysts said. A weaker dollar is generally seen as favorable for stocks by helping to keep global financial conditions loose.

“In reality the worst case scenario for equity investors would be a selloff in [Treasurys] accompanied by widening credit spreads and a strong dollar,” Darby said. “To date, higher U’S’ bond yields have not been able to arrest the decline in the greenback — real interest rates are still negative.”

So what should stock-market investors expect?

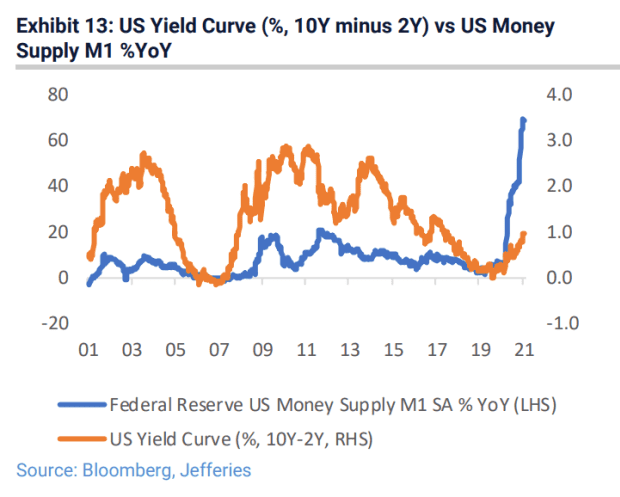

First off, “much higher yields,” he said, noting that all three of Jefferies’ indicators on the direction of the 10-year yield — the 10-year vs. 2-year U.S. yield curve vs. inflation expectations; the yield curve vs. U.S. M1 money supply; and the yield curve vs. the copper/gold ratio — are all pointed vertical, particularly the relationship between money supply and the yield curve (see chart below).

Jefferies

Jefferies expects the 10-year yield to hit 2% by year-end, Darby noted.

Secondly, high price-to-earnings ratio stocks in the S&P 500 saw a sharp absolute return as the 30-year Treasury yield

TMUBMUSD30Y,

plunged, Darby said (see chart below), noting the same was true for the tech-concentrated Nasdaq-100

NDX,

Jefferies

“These are the most sensitive to higher U.S. long-term rates,” he said, noting that equities are long duration assets.

The 30-year yield jumped 8.6 basis points to a more-than-one-year high 2.089% Tuesday, while the 10-year yield rose 9.8 basis points to 1.298%. The Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

eked out a gain of 64.35 points, or 0.2%, in choppy trade, building on last Friday’s record close as investors returned from a three-day holiday weekend. The S&P 500 ended 0.1% lower, while the Nasdaq Composite

COMP,

shed 0.3%.