WASHINGTON — Banking trade groups are facing pressure to revamp their political giving amid scrutiny of industry donations to GOP lawmakers who opposed certifying President Biden’s victory.

Donations to so-called Republican objectors drew attention after a mob of former President Trump’s supporters — believing falsehoods about the election outcome — violently stormed the U.S. Capitol Jan. 6 to stop Congress from finalizing the Electoral College result.

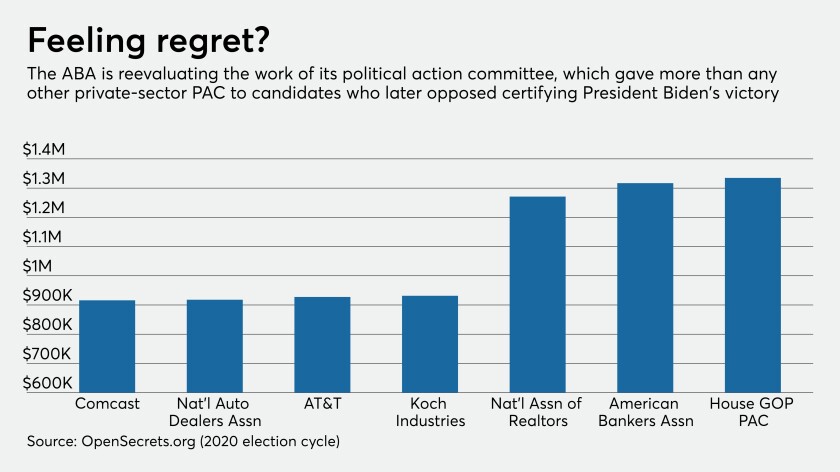

The American Bankers Association’s political action committee had given more to the 147 objectors — just over $1.3 million — than any other private-sector PAC, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

The center’s analysis for the 2020 election cycle, which predated the riot, ranked the top 20 PACs in donations to the objectors. The ABA’s total, first reported by the New York Times, was just behind that of a PAC established by House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif.

As the ABA and other trade groups reevaluate their political giving strategies, some election reform advocates say organizations need to look beyond traditional industry priorities when making fundraising decisions.

“I do think that there needs to be a much more thoughtful assessment about the individuals and groups that they are giving money to, that it’s not just about tax cuts and deregulation, but that it’s about their communities and their employees,” said Ann Ravel, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law and former Democratic chair of the Federal Election Commission.

The ABA along with the Consumer Bankers Association, Mortgage Bankers Association and Independent Community Bankers of America all said they were pausing campaign contributions for the upcoming campaign cycle to review their policies in light of the riots.

But a source close to banking trade associations, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said the announcements by the trade groups were not surprising since most organizations use the months following an election to reevaluate their spending anyway.

“There’s always about a three-month, four months [of] down time, while they retool for the new cycle and get the names of the new chairmen and subcommittee chairmen,” the source said. “That’s the process. So in early January, after the insurrection, it was easy for those associations to say that because they were doing that anyway. They were going to hold up their donations anyway.”

Some campaign finance reform advocates and industry representatives have criticized trade associations for pausing all political giving, rather than targeting members who voted against the certification of Biden’s election win.

“At least from what I’ve seen, that approach is not like winning a lot of sympathy, because it’s just transparently opportunistic and an effort to just see if this will all pass, and then you can keep going,” Weiner said. “It is not an approach that you would take if you actually care about holding the officials who tried to undermine our democracy accountable.”

Of the 24 Republicans on the House Financial Services Committee, 13 voted against certifying Biden’s election win, including Rep. Blaine Luetkemeyer, R-Mo., the top Republican on the financial institutions subcommittee.

A financial services lobbyist added that the trade groups’ temporary suspensions unnecessarily punish Republican lawmakers who did not object to the election result. In contrast, numerous corporations including AT&T, Comcast, GE, PricewaterhouseCooper and New York Life Insurance announced following the riot that they would specifically withhold donations for candidates that questioned Biden’s victory.

“Why should someone punish [Wyoming Rep.] Liz Cheney and [Senate Minority Leader] Mitch McConnell and [Missouri Sen.] Roy Blunt the same way that they’re punishing [Alabama Rep.] Mo Brooks and [Missouri Sen.] Josh Hawley?” the financial services lobbyist said. “If you think about it from that perspective, that doesn’t make any sense. Yet alone, why would you punish Democrats?”

Weiner said corporate PACs need to recognize longer-term that their decisions to contribute money to candidates based solely on industry-related policies have broader implications on society.

“That kind of siloed thinking is in some sense possibly what got us into this mess,” Weiner said, adding that it would be “quite something to hear from organizations that benefit From America’s political stability and basically the peaceful transfer of power, saying that they’re going to continue to subsidize candidates who tried to overthrow that.”

“So I would assume that they will be under a lot of pressure to take a different approach,” he said.

Eleanor Powell, a campaign finance expert and associate professor at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, said industry trade groups should evaluate candidates’ rhetoric when determining whom to support.

“Industry groups and contributors are going to have to weigh policies across a number of different issue areas and decide whether support of business-friendly tax policy or banking policy outweighs potential concerns of disinformation or conspiracy theories,” Powell said.

But others warned that trade groups would be straying from their mission if they backed candidates or planned donations on the basis of anything other than specific industry policy goals.

“My personal belief would be that a trade association should continue to give to people who support the interests of its members,” said Bradley Smith, a former Republican FEC commissioner and professor at Capital University Law School. “That’s the purpose of having a trade association PAC, or having the trade association contributions to Super PACs.”

Ravel argued that lobbying members of Congress on legislation favored by the industry doesn’t necessarily warrant contributing to a campaign.

“To just look at total deregulation in all arenas as a qualification for campaign giving without looking at some of the potential downsides of that contribution, which were evident with what happened in the invasion of the Capitol, … it seems that the entities, the banks and others should take into account how their constituents are going to respond to those things.”

But Smith said trade associations are partly intended to shield members by taking controversional positions on behalf of the whole group.

“I call it like being in the herd,” he said. “They get protection from being in the herd.”

A source associated with a state banking trade group that coordinates ABA on PAC donations also defended the policy of sticking to bank-related issues.

“The policy is we support people who support the industry that we work for,” the source said. “Other issues are simply irrelevant. I imagine ABA isn’t going to do anything other than listen to their bankers.”

But Ravel said that trade associations also need to consider their ethical obligations when giving to candidates.

“I think they should probably also have some kind of internal code or policy about political spending,” Ravel said.