For years now, some of the best, wildest, most moving or revealing stories we’ve been telling ourselves have come not from books, movies or TV, but from video games. So we’re running an occasional series, Reading The Game, in which we take a look at some of these games from a literary perspective.

There are games where the story exists only to knit together gameplay elements and action set-pieces. There are games where story is an afterthought entirely. There are games where story is the point, which live on the screen as vehicles for telling tales and offering players agency or immersion or both. And there are games where the story is something you invent yourself, taking the lead role in a movie written in every button-press and roll-dodge.

And then there’s Kentucky Route Zero.

It took seven years for the three-person team at Cardboard Computer to finish their masterpiece about a sad, regretful man making one last delivery for his employer’s failing antique shop. In 2013, Act 1 was a minimalist point-and-click adventure with a cliffhanger ending. It was about nothing at all — about a man named Conway and his hound dog in a sun hat trying to make a delivery to 5 Dogwood Drive, somewhere in the long dark of a mythical Kentucky night.

Conway was lost. In a hundred different ways, he was lost. In the past, in his regrets, in the moment. He was quiet, resigned — a man worn down to a nub even in the opening minutes, but still, you know, there. Still trudging forward. Still trying to do his job and find his way.

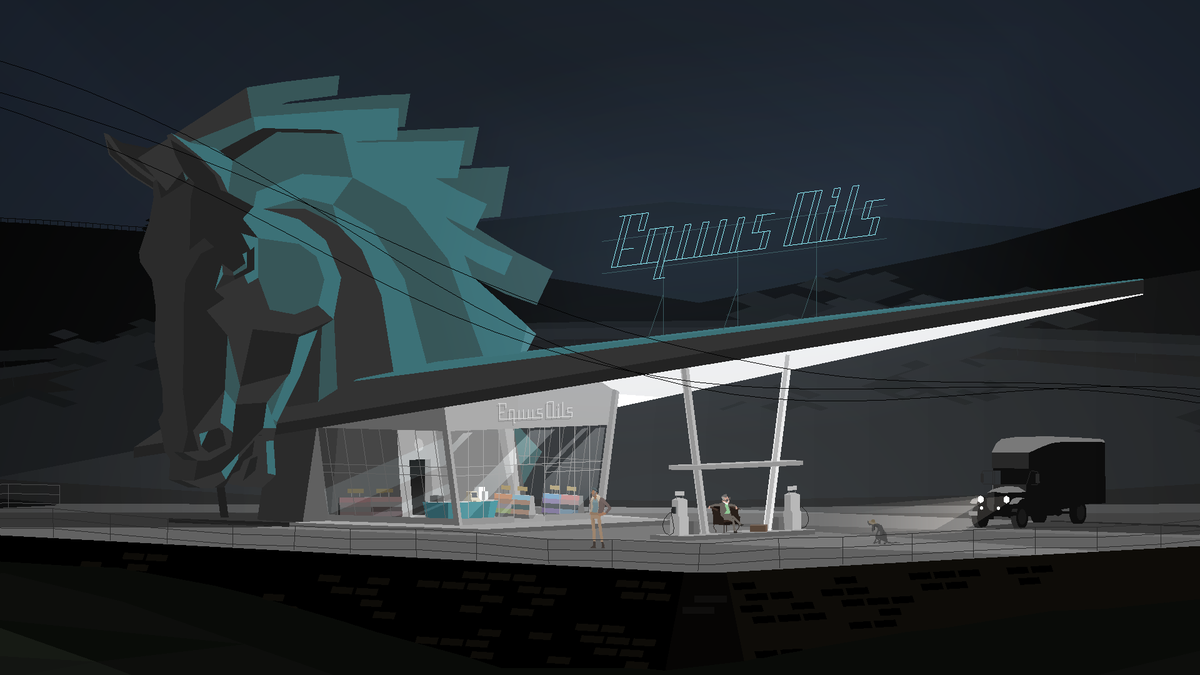

There was a gas station (blocky primary colors against an ink-black night) called Equus Oils, a blind man called Joseph, a broken computer. You go downstairs into the gas station’s basement and there are three friends playing a strange game around a card table, but they’re missing their 20-sided die. Find it for them and they vanish — gone without a trace, without explanation. Conway shrugs and moves on. Gets directions to a farmhouse “just past the burning tree that is always on fire” and meets Weaver Marquez. A transient mathematician whose life brushes up against the lives of a dozen other characters over the course of the full game, Weaver vanishes and reappears, is talked about more than she exists, is cryptic but never lies. Weaver explains to Conway that in order to find 5 Dogwood Drive, he’s going to have to take The Zero — a secret route through the caves running beneath the county, navigated by symbol, by sound, by memory.

And Conway says sure. Why not?

You say sure. Why not?

We all say sure. Why not?

And we’re off.

7 years, five parts, a series of interludes that are beautiful, haunting, heartbreaking and often all three at the same time — that’s the entirety of Kentucky Route Zero. It is a magical realist adventure, following in the traces of Gabriel Garcia Marquez (natch) and Neil Gaiman. It distorts reality and plays with surrealism like China Mieville and Haruki Murakami do, dropping references to Kafka and 100 Years of Solitude and Appalachian myths, all seasoned with a wicked, wry and weird sense of humor.

My favorite joke in the entire game? This one: At a certain point, fairly early on, Conway, his dog and Shannon Marquez (Weaver’s cousin) have to visit the Bureau of Reclaimed Spaces — a kind of super-bureaucracy that exists both on and just off The Zero, both inside and outside. A massive government edifice existing inside a former cathedral (complete with pipe organ), it is full of clerks and files cabinets, paperwork and crabs. You (as Conway) are presented with a list of elevator buttons. Floors you can visit. It goes like this:

Fifth Floor: (Diagrams and Drafts)

Fourth Floor: (Archives and Records)

Third Floor: (Bears)

Second Floor: (Conference Room)

First Floor: (Clerks’ Offices)

Lobby

Stop off on three and the bears do nothing. You walk through them and they just watch you. Hungrily, maybe. Or with boredom. Their big bear heads turn as you move through the floor. They watch you until, eventually, you leave. No comment is made about this. No mention. It just … exists. A floor full of bears.

Which is genius, really. Brilliant because the power of magical realism as a genre — the thing that makes it so spooky, so off-putting and able to get at the particular crawling dread of this modern century — is that every injection of the surreal, the impossible, the magical is treated the same way we’d treat the wind blowing or a lamp switching on. It is not unusual. It is not remarkable. Magical realism, on the page, is a tacit acceptance of the fundamental brokenness of reality (or, alternately, the mundanity of unreality) and the lack of commentary IS the commentary. In KRZ, it is a floor full of bears mixed in among the clerks and receptionists that no one notices at all.

The last broadcast from WEVP-TV.

Cardboard Computer

hide caption

toggle caption

Cardboard Computer

The last broadcast from WEVP-TV.

Cardboard Computer

When you walk back out again, there are crabs all over the ground. If you look at them, they’re wearing ink-jet cartridges and chains of paperclips as shells. Later, you will visit an art installation, see a barroom concert and a play, travel down a river to the ruin of a flooded town, suffer hallucinations, go into medical debt, get an electric skeleton leg, die (maybe), play some games, watch some TV (a lot of TV — including the final broadcast of a local public access TV station in a town wiped out by a flood which may stand as the single most affecting, haunting and strange sequence I have ever experienced in a game). You will be a man, a woman, a boy, a cat, a dog, a bird and a ghost. You will, depending on how you play, see many signs and wonders. You will (depending on how you play) learn or not learn many things. There’s no way you’ll walk away unaffected. Without a load of grief and wonder that you’ll puzzle over for days, turning it over and over in your mind until it takes on the texture of a dream.

And that should be enough, right? In a good game, even a great game, that would be plenty. For any story to crawl inside a person the way KRZ does? That’s miraculous and rare all on its own.

But what makes this game a masterpiece (best of a decade, maybe; best of its form, absolutely) is that it plays the way life plays. It is a story about unpayable debts, regret and hope, the way life is. It is fragmentary the way memory is. You miss a lot, no matter how thorough you think you’re being. You make choices that can never be unmade. With interactivity that revolves largely around pointing, clicking and making text-based dialogue choices, you’ll spin a yarn that is uniquely your own, discovering some things, missing others.

And in this way, the narrative unfolds with all the messy complexities of real life. People come and go. Names, references, fragments of the past, faded sketches and phone numbers scribbled in the backs of notebooks — this is the way that KRZ builds its universe. This is the way we build our own. And it never looks the same as anyone else’s. The choices you make along the way don’t matter at all, because we all end up in the same place. But then, the choices are also the only thing that matters because it is those choices that create the story we’re telling, and the one we’re being told.

There is no other game like Kentucky Route Zero. I’m not sure there ever will be again. It is a singular achievement — a deconstruction of American myth, a road-trip simulator, a vision of our world on the edge of dreaming that is more true and more real than almost anything seen in daylight. It is so full of bears and heartbreak that I could talk about it for a year without taking a breath.

But ultimately, it’s something you have to experience for yourself. Because only you will see it the way you see it.

Jason Sheehan knows stuff about food, video games, books and Starblazers. He is currently the restaurant critic at Philadelphia magazine, but when no one is looking, he spends his time writing books about giant robots and ray guns. Tales From the Radiation Age is his latest book.

Which is exactly the way it was meant to work.