In 1969, Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi nationalised 14 banks to help cement state control in the financial system.

Five decades later, Narendra Modi has taken the first steps towards undoing crucial parts of that legacy, breaking a decades-long taboo unveiling plans to privatise two of 12 state-owned lenders.

The measure was part of several market-orientated financial reforms unveiled in India’s budget for the year starting in April, including allowing foreign control of insurance companies after years of debate and creating a “bad bank” to buy up failed assets.

Even before coronavirus, India suffered from one of the world’s highest bad-loan ratios, a persistent obstacle to faster economic growth. But the urgent need to shore up government revenues and limit a destabilising rise in defaults after the pandemic forced the policy shift.

Many economists welcomed the proposals, calling them long overdue steps to liberalise a financial system unable to supply India’s growing economy with enough credit. Ila Patnaik, a professor at the National Institute of Public Policy and Finance and former government adviser, said the plans sent “a very important political signal”.

“For so many years, bank privatisation was off the cards,” she said. “The fact that it has been announced — even before you have a plan of which banks — is a very strong pro-reformist, pro-market signal.”

But economists also warned that progress hinged on Modi’s ability — and willingness — to see through potentially unpopular reforms. The prime minister is already fighting a political battle over a controversial market-friendly overhaul of Indian agriculture.

“It’s a good statement of intention,” said Rathin Roy, managing director of ODI London, a think-tank. “But there is nobody that I can see in the government that cares enough about privatisation and has the political capital to make this work.”

Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party has a patchy record when it comes to implementing reforms. It approved the sell-off of ailing state carrier Air India in 2017 but is still struggling to find a buyer.

Other initiatives such as his attempted black-money purge in 2016 were panned by economists as misguided and destructive.

Most recently, Modi’s attempt to reshape agriculture has prompted a fierce backlash. The BJP passed three laws allowing corporate participation in agricultural commodity markets in September, rushing them through parliament with minimal debate and consensus building.

Opponents said it encapsulated the BJP’s bulldozing governance style, stoking months of protest that have escalated into one of Modi’s greatest challenges.

Observers said his government would need to learn from those missteps if it was to champion the “political hot potato” of privatisation and foreign ownership in financial services.

“The larger issue is the government’s intent . . . It’s so popularity-driven,” said an adviser to banks in Mumbai. “It’s ability to rock the boat has not succeeded.”

Banks were nationalised to serve independent India’s development goals. But private banks such as HDFC and Kotak Mahindra have proliferated since India began liberalising its economy in the 1990s, especially catering to urban middle classes.

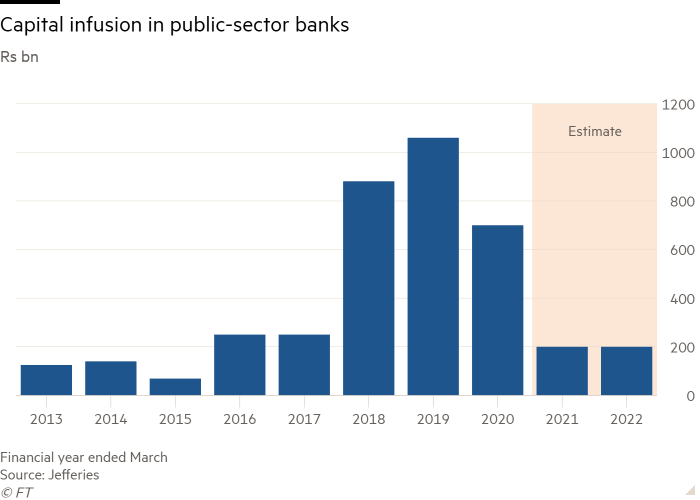

The banking system, however, is still dominated by state lenders, which account for about two-thirds of assets. While gargantuan State Bank of India is among the country’s most successful lenders, many require regular bailouts. In last week’s budget Nirmala Sitharaman, Modi’s finance minister, announced another Rs200bn ($2.7bn) bank recapitalisation.

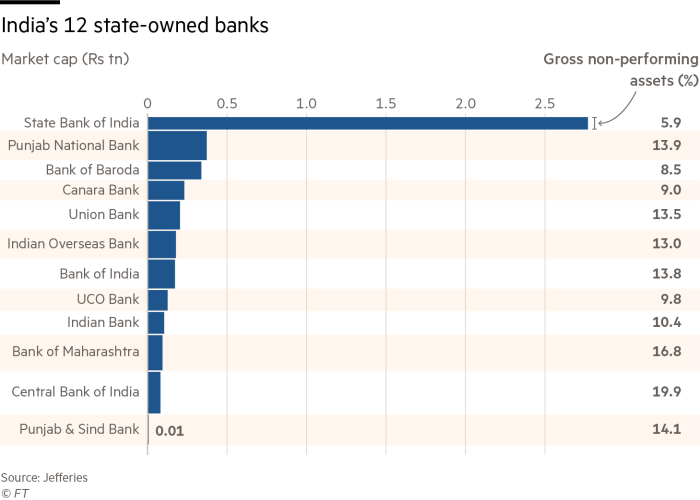

Weaknesses including operational inefficiency, susceptibility to political pressure and vulnerability to scandal marred state banks’ performance. Punjab National Bank was stung by an alleged $2bn fraud in 2018 over loans given to fugitive jeweller Nirav Modi. Private banks, too, have suffered their share of scandal.

The BJP has taken tentative steps to strengthen state banks, merging some of the weakest to reduce the total from 27 in 2017 to 12.

“There needs to be some balance between what is important for a development agenda versus privatisation,” said Gaurav Arora, Asia-Pacific banking head at research firm Greenwich Associates. Some privatisation will result in “a much more organised playing field” with both stronger state and private lenders.

Sitharaman also proposed increasing the cap on foreign direct investment in insurance companies from 49 per cent to 74 per cent. Foreign ownership in the insurance market has proved politically controversial since the sector was liberalised more than two decades ago.

She outlined plans, too, to set up an asset reconstruction company, or “bad bank”, to clean up lenders by buying bad assets and selling them to specialised investors.

It is unclear which of the 12 banks they would look to offload. Some speculate the likely candidates include Punjab & Sind Bank or Bank of Maharashtra, which are among the smallest and worst performing.

While more politically palatable than selling off stronger candidates, they may struggle to attract a strong valuation and buyers. Turning them around “would require so much [resolution of] non-performing loans and legacy staff that converting them is a nightmare”, said Abizer Diwanji, EY’s head of Indian financial services.

Montek Singh Ahluwalia, deputy chairman of the previous government’s planning commission, said the move would nonetheless set an important precedent.

“Privatising a couple of small banks will not make a significant difference to credit growth in the short run, but it eliminates something that was earlier sacrosanct as a principle,” he said. “It is a little like sticking your toe in the door for possible big change later.”